Generation Black TV - Live

The History of ‘Unwell Women’ by Elinor Cleghorn

“The history of medicine, of illness, is every bit as social and cultural as it is scientific,” Unwell Women, Elinor Cleghorn

‘Unwell Women: A journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World’ by scholar Elinor Cleghorn is an exposé of medicine’s treatment of women throughout history and how it tightly intertwines with misogynistic and patriarchal societal beliefs of the time. The book was inspired by her own experience with undiagnosed lupus.

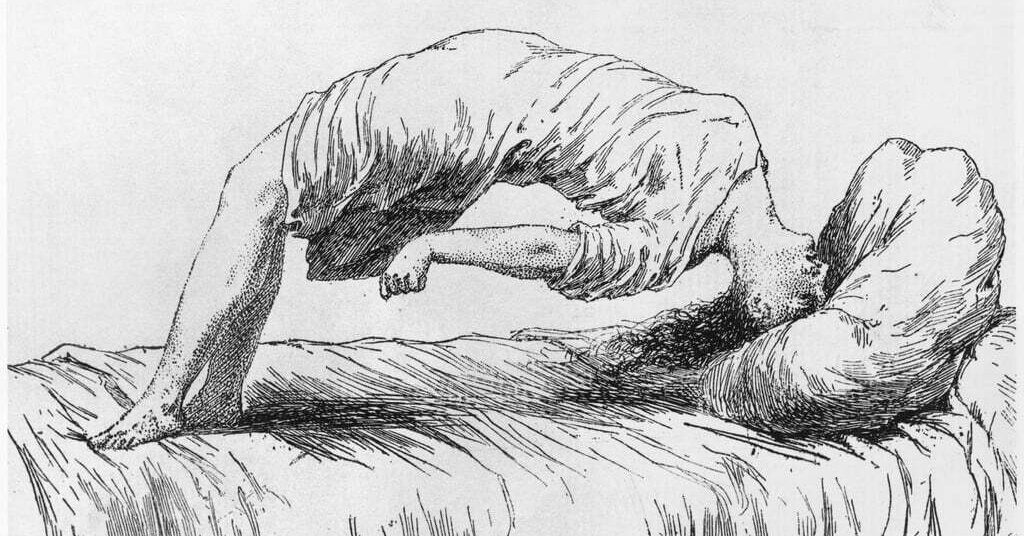

The domino effect of each prominent male medical figure onto the next is also explored, as the ideas of an untamed, feral womb and women as unreliable narrators of their own bodies are passed down through generations of medical practices. This piece is an incredibly eye-opening historical analysis, illuminating the seemingly echoing experiences of women throughout history as they face the ignorance and lies perpetrated by the healthcare providers placed on pedestals above them.

Opening the book is Cleghorn’s assertion that “the history of medicine, of illness, is every bit as social and cultural as it is scientific.” The introduction outlines how intertwined our ideas of gender and the nature of being human are and how gender divides often reflect patriarchal ideas. Modern medicine is described as male-dominated since its inception in Ancient Greece, where the one and only Aristotle described women as the inverse derivative of men, claiming that what made women, women is their reproductive capabilities. This sets the stage for her later timeline of healthcare and the butterfly effect of this ideology on the ongoing medical treatment of women.

The piece tells a dense chronological look at the healthcare of those deemed women throughout history and the intense oppressive views and myths they were subject to. The reader can connect their own experiences within the healthcare industry or beliefs they have been told about their own bodies to that of the unwell women featured within its pages.

After an impactful overview of the all too familiar dismissive treatment of women and AFAB (assigned female at birth) individuals by healthcare professionals and its intersection with racial identity, the author gives an impactful account of her struggles with getting answers for her health struggles and discovering that many others in her situation were also women.

She describes how she went down a rabbit hole of medical records, detailing the lives and experiences of women that came before her, mirroring her own. Her statement that “these women were part of my history… I felt an intimate kinship with them. We shared the same essential biology. What has changed is not the female body itself, but medicine’s understanding of it” is incredibly powerful and effectively lays out the core of the text as existing to give the women within its pages the dignity they deserved and to expose how and why myths about AFAB bodies came to be.

This critique of the definiting of women solely by their physiology is also used to discuss how who society deems as female does not always align with the complexities of gender. Not all who have a uterus are women and not all who are women have a uterus. However, in the eyes of medicine, the idea of female and uterus is cemented together. ‘Unwell Women’ becomes a narrative of male dominance over those they label as women due to their physical differences, rather than those who describe themselves as women. The text stands as a statement on how to discuss ‘female’ issues whilst respecting the identities of all those that are impacted by them.

This critique of the definiting of women solely by their physiology is also used to discuss how who society deems as female does not always align with the complexities of gender. Not all who have a uterus are women and not all who are women have a uterus. However, in the eyes of medicine, the idea of female and uterus is cemented together. ‘Unwell Women’ becomes a narrative of male dominance over those they label as women due to their physical differences, rather than those who describe themselves as women. The text stands as a statement on how to discuss ‘female’ issues whilst respecting the identities of all those that are impacted by them.

The origins of hysterics and other womb centric ideas, as well as why women’s symptoms are overlooked, become abundantly clear. Cleghorn describes Hippocrates’ knowledge that women’s difference from men comes solely down to her uterus and sets the foundation that Hippocratic practice. And, this still influences modern practice, namely via the Hippocratic oath, which was widely interpreted through a Christian eye and thus became highly socially influenced, rather than scientific and evidence-based.

Throughout history, women were denied knowledge of their own bodies and those who listened to their experiences, such as midwives, were barred from helping them, forcing reproduction, childbirth and menstruation to become increasingly pathologized and so, interpreted by men.

Later in the text, she describes how ideas of the ‘wandering womb’ were substituted with hormonal theories and old ideas about women’s bodies being naturally defective and deficient still pulsed through endocrinological theories. Originally, hormonal treatments were targeted at men to free their wives from the constraints of the menstrual cycle, then were marketed as a form of liberty to women themselves, telling them that to be free was to reject what medicine has pedalled as what made them women for as long as it has existed. This seemingly hypocritical change in view maintains the social control of women ageing back to the Christian influenced views of the docile, reproducing woman and even further to the idea that AFAB individuals are defective men.

The healthcare and societal understanding of AFAB individuals and their bodies have a long, long way to go. And, this is evidenced by Cleghorn’s account of her own experience attempting to get a Lupus diagnosis being met with suspicions of pregnancy and psychosomatic conditions and the real-life threat this ignorance has for women, as well as the medical misogyny far too many of us are familiar with. I highly recommend taking the time to read ‘Unwell Women’ to better understand the baffling, yet all too common, myths and disbelief met by the lived experiences of AFAB individuals even today.

My experience reading this book can be summed up in one word, anger. The character studies of some of the women forced into historical records to be poked, prodded and gawked at without thought or care of her autonomy left me horrified. The myths perpetuated about bodies like mine felt scarily familiar and the echoes from the continuous injustices faced by women throughout are easily connected with Cleghorn’s accounts of modern medical practice.

This text should not be taken as a historical retelling, but rather as a social analysis of medicine and femininity. Cleghorn’s PhD in Humanities and Cultural Studies, education in medical humanities and her status as a feminist advocate lend themselves well to the social aspect of historical medicine. However, the lack of medical knowledge comes through in some factual inaccuracies throughout the chapters.

‘Unwell Women’ is a must-read for those seeking to better understand their own, or their peers’, experiences within the medical field and in life.