Generation Black TV - Live

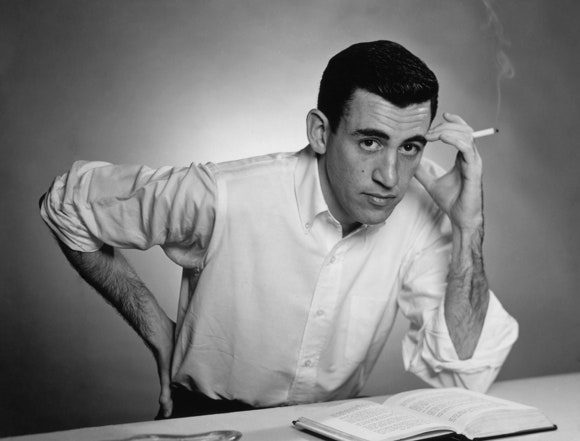

J D Salinger: Author Spotlight

Without World War II, J D Salinger, one of the most influential and controversial American authors of the 20th century, may never have been

J D Salinger was a talented and promising young writer who, at the peak of success, decided to withdraw from society and lead a silent private life – only to grow the mystery and popularity around his figure and turn himself into a legend.

Literary mythologies apart, the importance of Salinger’s works lies in a variety of factors – like the striking clarity of the writing, the influence of Oriental philosophies and religions and the ability to portray post-war American middle-to-upper-middle class in all its vanities and contradictions, to name a few. But, the main one is certainly the iconic characters: young rebels and gifted children with deep thoughts and interests who refuse to conform to middle-class mediocrity and are destined to be misunderstood by the materialistic American society; Salinger shapes them after his own self and experiences, using them as a vehicle for expressing freely his thoughts and discomforts or to exorcise his own trauma.

Jerome David Salinger was born in 1919 in an upper-middle-class family in New York; his parents’ resources could allow him to have the finest education, but his cynical and restless nature had other plans: he was expelled from multiple private schools until his father decided to send him to the military academy. There, “Jerry” developed a passion for literature and started to work on his characters. One of the first ones he created was Holden Caulfield, who will grow up to become the protagonist of The Catcher in the Rye and can be considered an alter ego of young Salinger: a wary and disillusioned teenager that embodies the author’s bitter and intolerant look towards society and its thriving superficiality and hypocrisy.

Salinger got his first published pieces – the two short stories The Young Folks and Go See Eddie – in the Story Magazine (run by Whit Burnett, who held a short-story writing course at Columbia University that Salinger attended). In 1940, being published, even by a small magazine, was a big milestone for any writer, but Jerry’s aim was to see his stories on the pages of The New Yorker: he proposed numerous works which were all rejected, until 1941 when the magazine finally accepted a short story featuring an embryonal Holden Caulfield. But, unfortunately, Salinger’s dream vanished rapidly: in December of that same year, the USA entered WWII and – given the circumstances – The New Yorker lost any interest in publishing a story about a rebellious teenage boy.

© Getty Images

In 1942, following the umpteenth literary delusion, J D Salinger joined the army; in 1944 he was sent to Europe, taking part in the Normandy landings – with six chapters of The Catcher in the Rye on him. Working on the novel mildly distracted him from the atrocities of the war, but it couldn’t save him from the profound impact what he witnessed had on Salinger’s psyche: at the end of the war, he spent a period in a hospital in Nuremberg to cure his nervous breakdown, but once landed back in America his look on the world changed forever.

Success arrived in 1948 when The New Yorker finally published A Perfect Day for Bananafish, whose protagonist is another unforgettable character: Seymour Glass, a WWII veteran who kills himself on his honeymoon. From this moment on, the enthusiasm around Salinger’s work grew steeply and reached its peak in 1951 with the release of his first and only novel, The Catcher in the Rye, which will become an international timeless classic.

Recognition eventually started to show its dark effects: Salinger’s intolerance of society made him gradually distance himself from the spotlight until he moved from New York to the small town of Cornish in 1953. The growing misanthropy would then result in cutting off any human interaction from 1980 until his death in 2010 – with the exceptions of some rare appearances at the local post office. The few people close to him confirmed that he never spent a single day of his solitary life without writing.

Recommended works:

- The Catcher in the Rye (1951). Seventeen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates what happened to him the previous year shortly before the Christmas holidays when he was kicked out of school – again. But, instead of waiting for the holidays to come back home and give his parents the unfortunate news, Holden escapes and wanders through the streets of New York to make up his mind. This novel has been a manifesto for angsty adolescents for decades: the protagonist’s absolute refusal to meet societal and family expectations, united with unexpected tenderness, sensitive observations and an unforgettable secondary character, make The Catcher in the Rye a powerful coming-of-age masterpiece.

- Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters and Seymour. An Introduction (1963). In these two short stories, writer Buddy Glass focuses on the tragic figure of his brother Seymour, who committed suicide during his honeymoon. The first story is the chronicle of what happened before, during and after Seymour’s messy wedding day; the second one is a detailed analysis of his brother’s supernaturally wise and charismatic persona and the precocious siblings’ childhood in the numerous and eccentric Glass family. In this work emerges Salinger’s interest towards child prodigies, as well as to confront his own post-war trauma and lost innocence.

- Nine Stories (1953). This collection brings together nine short stories published between 1948 and 1953, including the fortunate A Perfect Day for Bananafish. The diverse set of characters and situations make this book an essential read to fully understand the exceptionality of Salinger’s work: spanning from the gifted children we learnt to know to broken adults, these stories convey a sense of bitterness, misery and despair – what J D Salinger felt throughout his whole life. But, not everything’s lost, beams of hope lie in the youth, which is the last bastion of humanity, wisdom and purity in a corrupt and ugly world.