Generation Black TV - Live

Life of Brian: Monthy Python’s take on Religious Fanaticism and Political Hypocrisy

Monty Python’s Life of Brian provides interesting reflections on the themes of religion and political activism

Over 14 years, Monty Python established themselves as one of the undisputed cornerstones of British comedy. Coming from the sophisticated education of Oxbridge, the group’s humour is characterised by cultured references and a desecrating look at the institutions and values of our society, as shown in their numerous productions that range from feature films to tv sketches and live shows. Their 1978 film Life of Brian provides interesting reflections on the themes of religion and political activism and is a perfect example of their witty and thought-provoking style.

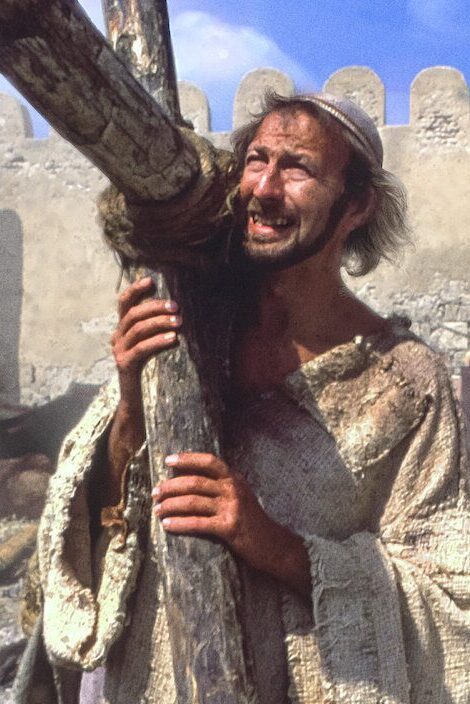

It’s the story of Brian Cohen, a young Jew from Nazareth whose life, since birth, always intertwined with that of a definitely more famous peer and fellow citizen: Jesus. Growing up in Roman-occupied Judea, as an adult Brian develops a shaky self-consciousness and loathing for the invaders. Brian’s life changes when he meets the People’s Front of Judea, a revolutionary group for the liberation from the Roman rule: after discovering that they have political interests in common, the organization thinks that Brian could be useful for the implementation of their subversive actions; this puts Brian under the authorities’ spotlight, but he always manages to run away.

During one of these escapes, Brian accidentally falls on a preacher’s pedestal and in order to save himself he improvises random phrases to the small crowd that has gathered below him but, in doing so, he’s chased by an increasing number of people who believe he’s the Messiah. Brian tries in vain to push his ‘disciples’ away, but the more he denies that he’s the Messiah the more they’re convinced of his holiness.

Brian is arrested and sentenced to crucifixion, but the PFJ refuses to save him as they believe that their cause needs a martyr; abandoned by the revolutionaries and by his mother, Brian has no choice but to accept his absurd end to the uplifting nihilism of Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.

Brian is essentially an adult stuck into adolescence: inexperienced, shy, full of doubts and dominated by an authoritarian and petulant mother; nevertheless, the germ of some form of political and social awareness begins to develop in him. The meeting with the People’s Front of Judea gives him the opportunity to get out of a condition of passivity and start a process of maturation, as well as to make him acknowledge the implications of fanaticism – both political and religious.

Life of Brian © Monty Python

Since their first appearance, the members of the People’s Front of Judea are presented as the stereotype of the passionate left-wing political activist: articulate thoughts and vocabulary and a taste for discussion. But it’s soon shown that these characters do nothing actually revolutionary, and are stuck in and endless limbo of rhetoric and insults towards other liberation parties. This fictional group embodies a sad tendency of politics, still true nowadays: the struggle of the Left to actually build a strong coalition, which allows the xenophobe and totalitarian right-wing dangerous rise. In the film, Judea’s numerous Fronts get lost in bickering, letting small dissonances divide them, instead of uniting and leading the uprise against the Romans.

Another scene that is worth considering is the one when one of the PFJ members comes out as a trans woman: this event is sceptically welcomed by the other activists at first, as they ridicule her for her wish to have babies, considering it a “struggle against reality”. While some people exploit this particular scene to horribly justify their transphobic views, many agree that it’s actually the contrary: the sketch aims at proving once again these activists’ incompetence as, when confronted with something that might bring them together and be an actual point of start for their action, they take it as just another thing to disagree on, as well as showing the hypocrisy of supposedly ‘progressive’ people who in fact fail at being open-minded in real life. Many wish to believe that this latter interpretation is true and it wasn’t Monty Python’s intention to be transphobic – although John Cleese’s views on the matter, as well as his position on the recent JK Rowling issue, leave many rightly dubious.

Given its themes, Life of Brian sparked outrage within the Church, which accused the film of being blasphemous as well as an attack on religion and the figure of Christ. In return, Monty Python has eloquently explained that the actual meaning isn’t to ridicule Christianity itself – or Jesus, who only appears for a few seconds and is left as a background character -, but it’s rather a critique on the unquestioned acceptance of beliefs and ideologies that feed fanaticism. Brian’s ‘disciples’ are fascinated by his harmless nonsense and, although their hysteria is exaggerated for laughs, it’s actually very reflective: in times of turmoil, people tend to seek references and meaning in their lives; some find this in religion and spirituality, but others – usually the weaker – are willing to follow anyone who promises them any answers.

History is full of examples of people that had their lives and minds ruined by these money-grabbing cult leaders or disciples who committed crimes blinded by their devotion; or furthermore, more recently, self-help gurus who charge people absurd amounts of money for their services, such as supposedly life-changing seminars filled with cryptic phrases and basic human knowledge. This said Brian’s helpless cry to his irrationally adoring crowd serves us the real message of the film: “You don’t need to follow me! You don’t need to follow anybody! You’ve got to think for yourselves! You’re all individuals!”.

Finally, Brian’s crucifixion is the tragicomic end of a man who just wanted to be left alone and, as the whistles of “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” give us a bittersweet smile, we’re left to reflect on whether life really has a supernatural, one-for-all meaning or if simply we have to make our own meanings ourselves.